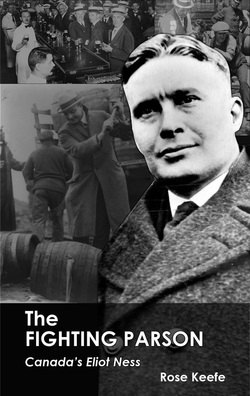

The Fighting Parson: The Life of Reverend Leslie Spracklin (Canada’s Eliot Ness)

Reverend Spracklin was a gangster’s worst nightmare. Known to the press and public as the ‘Fighting Parson’, he and his handpicked squad of dry agents burst into the roadhouses of Essex County with pistols drawn and fists clenched. They chased liquor-laden vehicles through dark city streets and along rough country roads, and intercepted rumrunners on the Detroit River in their high-powered speedboat, the Panther II.

The minister went, often alone, into the most dangerous nightspots of 1920s Windsor, and responded to opposition by punching, not preaching. He thought nothing of carrying around a stack of blank search warrants and filling them out himself as needed. He could not be scared or bought, and he survived one assassination attempt after another. It was only when a roadhouse owner who also happened to be a long-time enemy died at his hands that the campaign was finally stopped.

His life is told in this short book.

The minister went, often alone, into the most dangerous nightspots of 1920s Windsor, and responded to opposition by punching, not preaching. He thought nothing of carrying around a stack of blank search warrants and filling them out himself as needed. He could not be scared or bought, and he survived one assassination attempt after another. It was only when a roadhouse owner who also happened to be a long-time enemy died at his hands that the campaign was finally stopped.

His life is told in this short book.

Buy Now!

The Fighting Parson PDF and ePub |

Excerpt

Introduction As the Prohibition movement grew throughout North America during the early 1900s, most supporters signed petitions, attended rallies, and voted for pro-temperance politicians. But a handful took their dedication one giant step further. Carrie Nation, the elderly firebrand from Kansas whose response to the assassination of President William McKinley was “All drinkers get what they deserve”, smashed up saloons with her trademark hatchet. Ex-ballplayer and evangelist Billy Sunday dominated pulpits and stages with his show-stopping ‘Get on the Water Wagon’ sermon, and was famous for such dry slogans as “Whiskey and beer are all right in their place, but their place is in hell.” His histrionic speeches drew crowds and eased the passage of Prohibition into law.

The only thing that Canada’s Reverend John Oswald Leslie Spracklin had in common with Nation or Sunday was a fanatical hatred of the liquor traffic. He was no aging zealot conducting a purity campaign. When the Attorney-General of Ontario authorized him to enforce the Ontario Temperance Act in July 1920, Spracklin was a thirty-three year old Methodist minister who still retained the athletic build that he had cultivated as a college rugby player. With the power of the provincial government behind him, the charismatic clergyman bypassed vaudevillian tactics in favor of fighting the Windsor and Detroit area bootleggers and gangsters on their own terms. Historian C.H. Gervais described Spracklin as “a kind of teetotalling Wyatt Earp, who stopped at nothing to win.”[1]

The Toronto Daily Star, which had anticipated his appointment as a liquor license inspector (as Ontario Prohibition agents were called) for months, announced gleefully on July 31, 1920:

Bootlegging circles in Windsor and the Border Cities last night whispered the name of Spracklin over the wires in the same tones as did the English mother that of Black Douglas in the days of old, “Hush ye, hush ye, Spracklin will not get ye.”

“Don’t be so sure of that!” said Spracklin as he appeared unexpectedly in the … roadhouses….

Reverend Spracklin was a gangster’s worst nightmare. Known to the press and public as the ‘Fighting Parson’, he and his handpicked squad of dry agents burst into the roadhouses of Essex County with pistols drawn and fists clenched. They chased liquor-laden vehicles through dark city streets and along rough country roads, and intercepted rumrunners on the Detroit River in their high-powered speedboat, the Panther II. The minister went, often alone, into the most dangerous nightspots of 1920s Windsor, and responded to opposition by punching, not preaching. He thought nothing of carrying around a stack of blank search warrants and filling them out himself as needed. He could not be scared or bought, and he survived one assassination attempt after another. It was only when a roadhouse owner who also happened to be a long-time enemy died at his hands that the campaign was finally stopped.

Chapter One John Oswald Leslie Spracklin, or ‘Leslie’ as his friends and family called him, was born in Woodstock, Ontario, on December 4, 1886. His father, Joseph, worked as a harness maker while his mother, Charity, tended to her growing family. In 1894, when Leslie was eight, the Spracklins moved to Windsor, the southernmost city in Canada.

Windsor had been incorporated as a city only two years previously but was growing fast, largely thanks to the whiskey business. After the Great Western Railway selected Windsor as its termination point in 1854, Canadian and American business leaders hurried to set up shop there. One of them, a grocer from Detroit named Hiram Walker, opened a distillery that produced the now-famous Canadian Club whiskey. Walker also built homes for his workers and gradually developed a company town that was aptly named ‘Walker’s Town’. (It was later changed to Walkerville.)

It’s doubtful that the Spracklin family had many dealings in Walkerville. They were staunch Methodists, and regarded alcohol as a key factor in marital breakdown, spousal abuse, and other social ills. Most of Canada’s leading temperance advocates were Methodists. During the nineteenth century, their influence was felt even in cities as large as Toronto, where alcohol sales had been strictly controlled and anyone who violated the Lord’s Day Act risked serious punishment, earning the city the nickname of “Methodist Rome”.[2]

Leslie Spracklin was an active boy who grew into an athletic young man. He and two of his brothers, William and Arthur, showed boxing talent at an early age: Arthur even trained with the celebrated Tommy Burns.[3] Leslie also excelled as a rugby player, leading his school team to several triumphs. He ignored the bruises, black eyes, and other minor injuries incurred on the field, seeing them as a small price to pay for victory.

Although not outgoing, Spracklin got along with most people. He was well-spoken, polite, and liked by his friends. But there was one individual who was destined to be a lifelong thorn in his side: Clarence Beverly Trumble.

Spracklin and Trumble, who was nicknamed ‘Babe’ because of his good looks, had played together as boys back in Woodstock, but by the time they were teenagers in Windsor, the association had soured. They competed over everything: sports prizes, girls, and the esteem of their peers. The handsome and charismatic Trumble was the more popular of the two, which Spracklin resented. Their mothers, who had been childhood friends, tried to stop the feud, but to no avail. The mutual antagonism worsened when Spracklin went into the Methodist ministry and Trumble took over a roadhouse, but neither could have predicted the deadly turn it was destined to take.

******

[1] C.H. Gervais, The Rumrunners: a Prohibition Scrapbook. (Scarborough: Firefly Books, 1980) p. 119

[2] “The way we were in Toronto in 1892.” Trish Worron. Toronto Star. Nov 1, 2002. pg. A.29

[3] Toronto Star, July 31, 1920

The only thing that Canada’s Reverend John Oswald Leslie Spracklin had in common with Nation or Sunday was a fanatical hatred of the liquor traffic. He was no aging zealot conducting a purity campaign. When the Attorney-General of Ontario authorized him to enforce the Ontario Temperance Act in July 1920, Spracklin was a thirty-three year old Methodist minister who still retained the athletic build that he had cultivated as a college rugby player. With the power of the provincial government behind him, the charismatic clergyman bypassed vaudevillian tactics in favor of fighting the Windsor and Detroit area bootleggers and gangsters on their own terms. Historian C.H. Gervais described Spracklin as “a kind of teetotalling Wyatt Earp, who stopped at nothing to win.”[1]

The Toronto Daily Star, which had anticipated his appointment as a liquor license inspector (as Ontario Prohibition agents were called) for months, announced gleefully on July 31, 1920:

Bootlegging circles in Windsor and the Border Cities last night whispered the name of Spracklin over the wires in the same tones as did the English mother that of Black Douglas in the days of old, “Hush ye, hush ye, Spracklin will not get ye.”

“Don’t be so sure of that!” said Spracklin as he appeared unexpectedly in the … roadhouses….

Reverend Spracklin was a gangster’s worst nightmare. Known to the press and public as the ‘Fighting Parson’, he and his handpicked squad of dry agents burst into the roadhouses of Essex County with pistols drawn and fists clenched. They chased liquor-laden vehicles through dark city streets and along rough country roads, and intercepted rumrunners on the Detroit River in their high-powered speedboat, the Panther II. The minister went, often alone, into the most dangerous nightspots of 1920s Windsor, and responded to opposition by punching, not preaching. He thought nothing of carrying around a stack of blank search warrants and filling them out himself as needed. He could not be scared or bought, and he survived one assassination attempt after another. It was only when a roadhouse owner who also happened to be a long-time enemy died at his hands that the campaign was finally stopped.

Chapter One John Oswald Leslie Spracklin, or ‘Leslie’ as his friends and family called him, was born in Woodstock, Ontario, on December 4, 1886. His father, Joseph, worked as a harness maker while his mother, Charity, tended to her growing family. In 1894, when Leslie was eight, the Spracklins moved to Windsor, the southernmost city in Canada.

Windsor had been incorporated as a city only two years previously but was growing fast, largely thanks to the whiskey business. After the Great Western Railway selected Windsor as its termination point in 1854, Canadian and American business leaders hurried to set up shop there. One of them, a grocer from Detroit named Hiram Walker, opened a distillery that produced the now-famous Canadian Club whiskey. Walker also built homes for his workers and gradually developed a company town that was aptly named ‘Walker’s Town’. (It was later changed to Walkerville.)

It’s doubtful that the Spracklin family had many dealings in Walkerville. They were staunch Methodists, and regarded alcohol as a key factor in marital breakdown, spousal abuse, and other social ills. Most of Canada’s leading temperance advocates were Methodists. During the nineteenth century, their influence was felt even in cities as large as Toronto, where alcohol sales had been strictly controlled and anyone who violated the Lord’s Day Act risked serious punishment, earning the city the nickname of “Methodist Rome”.[2]

Leslie Spracklin was an active boy who grew into an athletic young man. He and two of his brothers, William and Arthur, showed boxing talent at an early age: Arthur even trained with the celebrated Tommy Burns.[3] Leslie also excelled as a rugby player, leading his school team to several triumphs. He ignored the bruises, black eyes, and other minor injuries incurred on the field, seeing them as a small price to pay for victory.

Although not outgoing, Spracklin got along with most people. He was well-spoken, polite, and liked by his friends. But there was one individual who was destined to be a lifelong thorn in his side: Clarence Beverly Trumble.

Spracklin and Trumble, who was nicknamed ‘Babe’ because of his good looks, had played together as boys back in Woodstock, but by the time they were teenagers in Windsor, the association had soured. They competed over everything: sports prizes, girls, and the esteem of their peers. The handsome and charismatic Trumble was the more popular of the two, which Spracklin resented. Their mothers, who had been childhood friends, tried to stop the feud, but to no avail. The mutual antagonism worsened when Spracklin went into the Methodist ministry and Trumble took over a roadhouse, but neither could have predicted the deadly turn it was destined to take.

******

[1] C.H. Gervais, The Rumrunners: a Prohibition Scrapbook. (Scarborough: Firefly Books, 1980) p. 119

[2] “The way we were in Toronto in 1892.” Trish Worron. Toronto Star. Nov 1, 2002. pg. A.29

[3] Toronto Star, July 31, 1920